|

||||||

|

THE GOLDEN ROSARY OF THE KAGYU Reviewing the lives of our lineage ancestors, by Lord Marpa of the Southern Cliffs When we last looked in on our lineage forefather Naropa, he was residing at Pullahari monastery, awaiting the predicted arrival of his future student, the Tibetan Marpa ». Lord Marpa was born in 1012 in the central province of U, to wealthy landowner parents. Possessed from his earliest years of an unruly temperament -- today we might label him hyperactive -- he decided, with his parents' encouragement, to study the Dharma in order better to channel his wayward energies. Taking his share of the family inheritance early, he journeyed to India -- no small feat at the time. Not only did he have to traverse 700 miles and descend ten thousand feet, but like all travelers in those times he risked being robbed -- or worse -- by the many bandits who roamed the roads waiting for the unwary, gold-laden pilgrim to pass by. Because of the need to adapt to climate and altitude changes Marpa tarried in Nepal for three years, using the time to further his study of Sanskrit and colloquial Tibetan dialects. In the process he met Nyo Lotsawa (the world Lotsawa means “translator,” and comes from the Sanskrit lokchakshu, “light of the world” -- an indication of the esteem in which scholars were then held), who would prove, albeit in largely negative ways, to be a catalyst to Marpa's growth. Together, they encountered two disciples of Mahapandita Naropa, and just through hearing the latter's name, Marpa felt an awakening Dharma connection. Because Nyo did not share this connection, he and Marpa parted company, but Marpa traveled on to Pullahari monastery to meet his predestined teacher. Naropa gave Marpa the empowerment for the Hevajra tantra. Meeting up with Nyo a year later while taking a brief break, Marpa compared notes, but the jealous Nyo, seeing that Marpa's understanding of the Hevajra surpassed his own, made light of the Hevajra, saying it was already practiced in Tibet, and that if Marpa wished to do something truly significant he should request initiation into the Guhyasamaja Tantra. Returning to Naropa, Marpa requested this tantra, but Naropa instead sent him to Jnanagharba. Thus began a pattern in which Naropa repeatedly sent Marpa to other teachers, not because he wasn't perfectly capable of conferring the empowerments himself, but because the other teachers held special transmissions of the tantras in question and so were considered “pure sources.” This distinction was deemed important less for Marpa himself than for the integrity of the lineage and its continuance in Tibet. Among the teachers Marpa thereby studied with were Kukuripa, a mahasiddha living on an island in the midst of a “boiling poison lake” (probably sulfurous), who initiated Marpa into the Mahamaya, and Maitripa from whom he received the transmission of Mahamudra and the Six Yogas of Naropa. Having spent twelve years gathering these teachings and their accompanying texts, Marpa was running low on gold, and was therefore obliged to return to Tibet to replenish his supply for his next trip to India. En route, he met again, as he had periodically through the years, with Nyo Lotsawa, who was still in the grip of jealousy over Marpa's superior accomplishments. Giving in to his baser instincts, Nyo bribed his servants to throw all of Marpa's texts, so hard won and intended for the benefit of Tibetans, into the Ganges, as if by accident. Taking stock of this incalculable loss, Marpa momentarily considered throwing himself into the river as well. But he restrained himself, reasoning that if he were to be a serious Dharma student he must so mix the Dharma with his mind that he would no longer need the books anyway. He did, however, berate Nyo, albeit in skillful and rather restrained terms. “Today, you should abandon the name of guru, dharma teacher, and lotsawa,” he said. “ With remorse and repentance return to your country. Confess your evil deeds and do rigorous penance. Thinking and acting as you have done, and boasting that you are a guru -- though you might deceive a few fools, how can you ripen and free those who are worthy? Please do not cultivate the three lower realms.” With that the two parted, and we do not hear of Nyo again. Returning to Tibet, Marpa began gathering worthy disciples, giving to each one of the major teachings he had received in India. These students in turn passed on what they had received to yet other gifted disciples, thus causing the Dharma, like ripples emanating from a pebble tossed in a stream, to spread throughout Tibet. Marpa returned to India a second time to see his teachers again, review his understanding of their instructions, and gather a set of replacement texts to bring back to Tibet. Returning home he married, had a number of biological children, and attracted yet more Dharma “sons,” one of whom was Milarepa ». We will examine Milarepa's life story further on, but for the moment suffice it to say that the latter one night had a dream in which a dakini instructed him to obtain teachings on the Phowa, the ejection and transference of consciousness. After relating this to Lord Marpa, the two looked through all the latter's texts, but couldn't find the Phowa teaching. This determined Marpa, who had promised the Indian masters that he would return once more, to set out on his final trip to India. This journey was undertaken against the wishes of all Marpa's family and disciples, who felt that the great translator/teacher was now too old to withstand the rigors of such an expedition. In fact, they even hid his gold to prevent him from leaving, but so determined was Marpa that he vowed to head to India anyway. Marpa finally reached his intended destination, only to learn that Naropa had “entered the action” -- a phrase meaning that Naropa had achieved so advanced a meditative state that he could appear or disappear from the human realm at will. After many months of supplication and only the most fleeting glimpses of Naropa, Marpa finally encountered him in a forest. When he offered Naropa a mandala of all the gold he had painstakingly collected in Tibet, the latter said he had no use for it, but that he would accept it to bring merit to the disciples who had helped Marpa gather it. Whereupon, after offering it to the Triple Gem, Naropa threw it into the forest! Seeing Marpa's crestfallen look, Naropa joined his palms together, opened them again, now filled with the gold, and returned the offering to Marpa, saying: “I don't need this. If I needed it, this whole earth is gold.” And stabbing the ground with his big toe, he indeed turned the earth to gold. This was Naropa's teaching on sacred outlook. Marpa then asked for the Phowa teachings, at which the prescient Naropa countered, “Is this your idea or that of someone else?” When Marpa replied that it was Milarepa's request, Naropa again joined his palms, bowed three times in the direction of Tibet, and uttered the famous ode:

“In the gloomy darkness of the north,

And with that all the trees and mountains in the Pullahari region bowed three times, and are said to be inclined in the direction of Tibet to this day. It was during this same visit that Naropa, as a test of his student, manifested the Hevajra mandala, asking Marpa to whom he would bow first: to the vision of Hevajra, or to himself, Naropa, its creator. Overwhelmed by the grandeur of the Hevajra deity and retinue, Marpa made the mistake of bowing to the emanated mandala first. Naropa immediately corrected him, saying in effect that the guru always takes precedence because it is he who makes the deities real for us. But the damage was done, and Naropa warned Marpa that this was an omen that his biological descendants would die out, but that his spiritual lineage would continue as long as the Buddha's teachings continued. So distraught was Marpa over his error that he fell mortally ill and came close to death thirteen times. However, Naropa consoled him and named him as his regent. So Marpa left India for the last time, returning to Tibet where he consolidated his reputation as a teacher. Not everyone was drawn to him, however. Outwardly, Marpa had all the appearances of a worldly person with his family, household, land holdings -- and his fondness for barley beer! So occasionally he performed miracles (though this practice is generally discouraged) such as transferring his consciousness to the body of a dead pigeon while his human form appeared momentarily lifeless. (Interestingly, he later reported, “While my mind inhabited the body of a bird, it appeared to be dull,” showing that while consciousness is ultimately dominant, its relative connection with the body is undoubted.) He also explained that though his lifestyle appeared the same as that of an ordinary householder, it differed in essence because he was not attached to sense pleasure. Marpa also underwent the trial of losing his biological son, which though tragic also proved the power of the practices he had accomplished and transmitted. Tarma Dode, of all Marpa's children, was the one most gifted in his understanding of Dharma. One day, after departing a fair at which he was the honored guest, Tarma fell from his horse, who had been startled by shrieking birds. This was serious enough, but in addition his foot caught in the stirrup such that he was dragged until his skull was fractured in eight places. Despite his mortal injuries, the lad retained his composure, insisting on riding upright the rest of the way home. Standing before his horrified parents and the assembly of son disciples, he said: “Since by the kindness of my father I have the Phowa teachings, I will not have to experience the bardo. Therefore, don't be upset.” At the time of Tarma's passing, the disciples tried to find the body of a recently dead youth, but all that was available was the body of -- once again -- a pigeon. Tarma Dode successfully transferred his consciousness to the bird's corpse, and ultimately flew at Marpa's command to the Cool Grove Charnel Ground in India. There, he found the body of a recently dead Brahmin boy, and once again transferred his consciousness, taking on this new human form. Since the word for pigeon in the local dialect was tiphu, Tarma Dode was called Tiphupa, under that name ultimately becoming renowned as a great teacher. Interestingly, he later gave some of the teachings he had received in Tibet from Marpa to Rechungpa, one of Milarepa's major students. Rechungpa in turn brought these back to Tibet, so that branch of the teachings came full circle. Meanwhile, back in Tibet the son disciples questioned Marpa about the future of the lineage now that Tarma Dode was removed from the picture. Marpa instructed each of his four major students to examine their dreams and report back to him. The result of these nighttime visions was that Tsurton Wangne was to teach the Phowa in the East; Ngokton Chodor was to propagate the Hevajra Tantra in the South; Meton Tsenpo was to spread the teaching of Luminosity in the West; and Milarepa would establish Tummo (the yoga of psychic heat) in the North. In this way the essence of what Marpa had received in India from Naropa and others beamed across the snowy land of Tibet like the rays of the sun. At age eighty eight Marpa announced, “Glorious Naropa has arrived to take me to the celestial realm,” and with that he passed into the expanse of space amidst sounds of ethereal music and showers of flowers. Marpa's next incarnation arose again in Tibet as Trungmase Lodro Rinchen, who became a student of the Fifth Karmapa, and whose tulkus are of the lineage of Trungpa. So when speaking of Marpa's life we are also, in a sense, speaking of Trungpa Rinpoche.

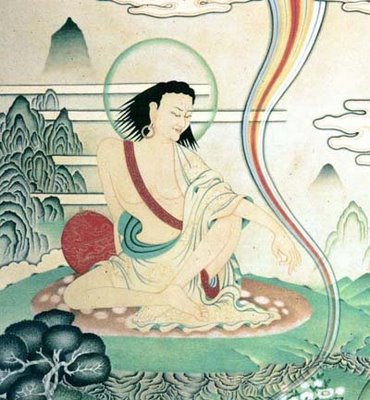

It has already been noted that Milarepa » was one of Marpa's chief disciples, but his road to his teacher was a hard one. Initially, his birth circumstances appeared auspicious. He came into the world in 1052, his father, Sherab Gyaltsen, being a wealthy trader, and his mother a strong-willed and respected woman named White Garland. Immediately upon hearing of Mila's birth, Sherab Gyaltsen named him Thopaga, meaning “Good News.” Four years later, Mila's sister, Peta, was born, and the fortunate family enjoyed means and prestige while living in their spacious home, Four Columns and Eight Pillars. (It was common in those days to name houses this way to denote their size.) All was serene until the day -- Mila was now about seven years old -- when his father became ill. Foreseeing that he wouldn't live long, Sherab Gyaltsen called his brother and sister to his bedside and entrusted to them all his family's worldly affairs until such time as Mila reached his majority. “After my death I will be watching you,” he admonished. “Take care of my wife and children.” No sooner did Sherab Gyaltsen pass out of his human form than the rapacious brother and sister made off with most of the contents of Mila's home, rendering White Garland and the two children virtually penniless. The family's clothes became ragged; their once luxuriant hair, so the story goes, grew dull. Further, what started out as public sympathy soon grew to contempt as White Garland made no apparent effort to regain the family's property. However, when Mila turned 15, an age at which he was considered old enough to establish his own household, White Garland, gathering what few resources she could call her own, threw a party to which she invited the greedy Aunt and Uncle, plus other relatives, friends and neighbors. She announced that the celebration was to mark Milarepa's majority, that he was now ready to marry Zesay, the girl to whom he had been betrothed since childhood, and that together they would be establishing their own household. Under the circumstances, she said in front of all these witnesses, it was appropriate that the Aunt and Uncle restore Milarepa's possessions and allow him to assume his patrimony. Feigning shock and offended feelings, the erring relatives claimed that the money and articles they had taken had never belonged to the deceased Sherab Gyaltsen in the first place, that to the contrary they, the Aunt and Uncle, had loaned all these goods to their brother, and that given the sumptuous feast White Garland had prepared it was clear she had enough money to squander! As we often encounter in the lore of these times, White Garland had one, then-standard response: she fainted! And the months passed with life going on as before. All the while, however, White Garland's resentment was growing until it finally boiled over in a manner that would be life-changing for her son. It happened in this way: Mila was invited to a wedding in the company of his tutor. Predictably, the two became a bit tipsy on chang (barley beer), and upon leaving the feast stumbled home somewhat unsteadily, all the while singing loudly. Hearing this (to her) unseemly display, White Garland ran out of the family home, threw soot from the hearth in Mila's face, and berated him soundly for making merry at a time when the family was suffering so deeply. There was only one way to obtain some shred of satisfaction, she told him, and that was for him to leave home and study with a master of the black arts so as to annihilate the Uncle, Aunt, and all those villagers who, though seeing the injustices leveled upon the family, did nothing to intervene. Dutiful son that he was, Mila soon set off to find such a master. Before long, Mila was directed to Yungton Trogyel (Terrifying Conquerer), known for the power of his spells and incantations. Mila stayed at the feet of this master for a year, but did not make much progress. Being moved by Mila's good service to him, and by his conscientiousness in trying to carry out his Mama's wishes, Yungton sent Mila a little distance away to a friend he thought would prove a more effective teacher. After arriving, Mila built his own retreat hut and worked single-pointedly for two weeks, invoking the guardian deities and telling them exactly whom and how many he wished killed. Meanwhile, back at home the Uncle and Aunt were preparing a wedding feast for the Uncle's eldest son. But the celebration was not to last long. A servant entered the stables in time to witness a giant scorpion, large as a yak, grasping the pillars of the house and tearing them asunder. The horses, in turn, took fright and finished whatever destruction the scorpion had left undone. The result was that thirty-five people were killed, excluding (this was by plan) the Uncle and Aunt. When invoking the deities, Mila begged them to spare these deceitful relatives -- not out of compassion, but so they would live long enough to recognize the full extent of the catastrophe, and suffer -- to the last drop -- the resultant grief. Milarepa was aware of his success, but he did not stop there. Returning to Yungton Trogyel, he announced that he wanted to kill yet more people -- specifically, those villagers who had stood by dumbly, refusing to help even in the face of clear injustice. The teacher agreed, and gave Mila instructions on how and when to produce a violent hail storm. As it happened, the harvest was particularly abundant that year, so when Mila effected his dark magic, the loss of crops -- not to mention the resultant deaths of people, animals, and small birds -- dealt the village an exceptional blow. And Mila, whom everyone suspected was behind these events, became a pariah throughout the land. Initially, Mila took satisfaction in his skill -- a pride which appears to have outweighed any thoughts of revenge, for one senses that even in those early years Mila was a basically good soul who was moved to act much more out of filial duty than anger. Certainly, at no point does he express hatred of his relatives, though he does ultimately berate them, as we will see further on. Meanwhile, however, his conscience began to bother him severely. As he reflected on the numbers he had killed and the ruin he had brought to his neighbors' livelihood, guilt so gripped him that, as he put it, “When I was out I wanted to be in, and if I was in I was restless to go out.” He could neither eat nor sleep. Serendipitously, however, his teacher, Yungton Trogyel, began experiencing the same qualms. When a wealthy benefactor died, the truth of death and impermanence became real for this master of black arts, and he began regretting both the harm he had brought on many, and the harm he had trained his students to do. Since he was growing old, however, he questioned his ability to enter into an intensive Dharma practice himself, and so offered Milarepa the chance to do it for them both, with his support. Of course, this fit in perfectly with Mila's plans, and on Yungton's advice he went to a Nyingma lama known for his speedy methods for bringing students to enlightenment. But as it turned out, Mila's lack of karmic link with this lama, added to the fact that his skills and speed in creating hailstorms had made him complacent, caused him to fritter away his meditation time and emerge without result. The lama then advised him to seek Lord Marpa with whom, the former felt, Mila had past life associations. Merely hearing Marpa's name filled Mila with happiness, so he set off with his meager belongings on his back. When he ultimately found Marpa, he told him the story of his life, including confessing his ill deeds, and begged for teaching. Marpa replied that he would give the teachings, but only after Mila had created a hail storm which would severely harm those bandits who had been attacking students coming from the U and Tsang regions. When Mila complied and reminded Marpa that he was supposed to receive teachings in exchange, Marpa flew into one of his famous rages and scoffed at the idea that the precious teachings should be given at the price of a few skimpy hailstones! Wherewith, he commanded Mila to cast hail on the mountaineers from Lhotrak who were attacking disciples coming from Nyel Loro. Mila's success earned him the title of Great Magician, but still Marpa was obdurate on the matter of the teachings, even berating him for piling more crimes atop his old ones. Thus was launched a series of episodes that repeated themselves approximately according to this pattern: Mila would ask for teachings; Marpa would agree, with the provision that Mila accomplish some Herculean task; Marpa would criticize or later claim he had never asked that such a task be done; Mila would despair and run to Marpa's wife, the ever-nurturing Dagmema; refreshed, Mila would summon his patience and try to appease Marpa once again. Among the most grueling and frustrating of the tasks that led nowhere involved a series of towers Marpa asked Mila to erect for Marpa's son, Tarma Dode. First, Marpa asked for a round tower to be built in the eastern direction, but after Mila had dragged a number of truly back-breaking stones into place, Marpa said he hadn't sufficiently considered the location, and that he instead wanted a semicircular tower placed in the west. This process repeated itself four times, during which Mila was allowed no assistance. He therefore had to dismantle each tower by himself, replacing all the stones from whence they came before starting the next tower. Meanwhile, the hard labor was causing Mila to develop infected sores all over his back. Throughout all this, however, and despite his mental and physical agony, Mila never lost faith in Marpa. But having still not received any significant teachings, Mila one day reached a point of despair that pushed him to the brink of suicide. Seeing the depth of Mila's commitment, the irascible Marpa softened and instructed Dagmema to bring Mila into the shrine room, saying: “Today Great Magician is guest of honor.” And in a scene worthy of grand opera, Marpa sat on his throne center-stage, so to speak, presiding over Mila, Dagmema, and all the assembled company gathered at his feet. He then gave the following explanation for his many actions that had outwardly seemed cruel or capricious, but in fact had been crafted expressly to neutralize the negative karma set in motion by Mila's ill deeds. “If everything is carefully examined,” Marpa began, “not one of us is to be blamed. I have merely tested Great Magician to purify him of his sins... Although my anger was like a flood water, it was not like worldly anger. However they may appear, my actions always came from religious considerations. Had this son of mine completed nine great ordeals, his full Enlightenment would have been achieved. Since this didn't take place, there will remain a faint stain of defilement with him. However, his great sins have been erased. Now I receive you and will give you my teaching.” Mila, later recalling the moment, described it in very human terms: “As he was saying these words I wondered: Is this a dream or am I awake? The mistress [Dagmema] and others thought, ʻWhat skill and power the Lama has...He is a living Buddha.' And their faith grew still more.” After giving Mila the lay vow and bodhisattva precepts, Marpa sent him into retreat for eleven months, during which he meditated continuously with a butter lamp on his head. Nor would he move until the lamp went out. He would emerge for brief spells to report his progress to the Lama and his wife, but soon enough he would head back for the retreat cave. It was during this era, while in deep meditation, that he had the vision of a dakini telling him to lay hold of the Transference of Consciousness teachings. And as we have already seen, it was this vision which led Lord Marpa to make his third -- and final -- trip to India. Meanwhile, Mila remained several years meditating in the area, while Marpa and Dagmema supplied him with his basic needs. All went well until he had a dream of his old home which appeared to have fallen to rack and ruin, while his mother was dead and his sister reduced to beggary. Awakening, Mila was overwhelmed with the desire to return home and check on things for himself. Marpa was not wholly happy, but eventually permitted Mila to go, telling him they would not meet again in this life. He also instructed him to dispense with all profit motive when offering teachings; not to put his disciples through the same level of hardships Mila had himself endured, because the newer students didn't have the same level of emotional stamina; and to spend his life primarily meditating in caves. When Mila arrived home, he discovered that everything he had seen in his dream had been true: the family house was in ruins, his sister had disappeared, and his mother's bones were lying in a heap on the floor. Overcome with depression, Mila, from the depths of his being, vowed never again to be distracted by samsara, but to meditate day and night and to kill himself if he so much as thought of worldliness. Eventually, Mila ran out of provisions and decided to go begging for food. However, with karmic inevitability he landed in the tent of his Aunt! The latter, still angered by the destruction Mila had wrought with his spells, unleashed her dogs on him, causing him in his weakened condition to fall fainting into a pool. When he recovered consciousness, Mila sang her one of his now-famous dohas (spiritual songs) in which he reminded her that it was her own evil deeds that had initially brought misery onto the family. Grudgingly, the Aunt gave her nephew some stale left-overs before he once more took to the road. Pursuing his search for alms, Mila soon came across another hostile tent inhabitant....his Uncle! No more pleased than his sister with Mila's sudden appearance, the man shot him with arrows. Mila fended him off by threatening to direct his old black arts against him. In reality, Mila had no intention of doing so, but he found this to be an effective deterrent. In due course, Mila reached Horse Tooth White Rock Cave where he settled for some time, engaging in the deepest austerities. When he ran out of food, he subsisted on the nettles growing at the cave opening, and these he ate for so long that his very complexion turned green. Moreover, when his clothes turned to rags he refused to mend them, reasoning that since he could die that very night, it would be more profitable to meditate. Eventually, both Zesay, to whom he had been betrothed, and Peta, his sister, discovered his whereabouts, visited his cave, and were stunned by his appearance. Whereas other so-called teachers were living in opulence, supported and cosseted by their adoring followers, Mila was emaciated, sunken-eyed, coarse-haired and nearly naked. Exclaiming in horror that they couldn't believe such a lifestyle led to happiness, they were countered by Mila's songs of joyous realization. One such ran, “Alas, how pitiful are worldly beings! Like precious jade they cherish their bodies, yet like ancient trees they are doomed in the end to fall.

“Though you gather wealth as hard

By now Mila had achieved many siddhis (miracle powers). He could levitate, shape-shift, visit Buddha realms, and fly. Bit by little his fame as a practitioner and the authenticity of his songs of experience won over Peta and their Aunt, the latter eventually begging forgiveness, studying the Dharma, and becoming an accomplished yogini. In addition, Mila attracted many very gifted disciples, chief among them Rechungpa, known as Dawa tabu (the Moon-like one), and Gampopa, known as Nyimatabu (the Sun-like one). Of the latter we will speak in depth a little further on, as he became the next lineage holder of the Karma Kagyu. But not everyone held Mila in esteem. At this time, there existed a rich, powerful Lama known as Geshe Tsakpuhwa, who was envious of Milarepa's greater fame, and nourished a grievance, besides, because once, after prostrating before Mila, the Geshe did not receive the anticipated prostration in return. In due course he hatched a plot to rid himself of his rival by getting his concubine to present Mila with a poisoned yogurt drink. The clairvoyant Mila knew exactly what the woman had been put up to, and for a time he put off drinking the potion, but after giving his disciples final instruction he agreed to ingest the tainted offering. After it became known that Milarepa was manifesting signs of illness, Geshe Tsakpuhwa appeared before him, hypocritically protesting his sorrow over Mila's condition and offering to take on the illness in his place. Mila replied that if he were to transfer his illness to the Geshe, the latter couldn't bear it, so he would transfer it to a door in the room instead. And with that the door in question split apart! The Geshe was unimpressed by what he termed a mere magic trick, at which point Mila transferred half the illness to him. After collapsing in agony, the Geshe finally realized what he had done, begged Milarepa's forgiveness, and offered him everything he owned. Mila declined the offer, but warned the Geshe never to commit evil deeds again. Further, Mila did something nearly impossible to effect: he took the Geshe's bad karma onto himself. “May the consequences of your karma be assumed and transformed by me,” he said, at which the Geshe promised to spend the rest of his life meditating. He also gave all his worldly possessions for the upkeep of the sangha. And so, at age 84, Milarepa passed into nirvana amidst manifold auspicious signs, such as showers of flowers, interlacing rainbows, and clouds assuming the shapes of lotuses. It was said that on that day harmony was so pervasive that gods and men conversed with each other.

Gampopa », as already mentioned, was one of Milarepa's most gifted students and his lineage heir. Predicted by the Buddha in the White Lotus Sutra of Compassion, Gampopa was born in 1079 and became an accomplished physician by the time he was 16 years old. Adopting the householder's life, he had a wife, son, and daughter, but within a few years all three had perished of an epidemic which Gampopa was unable to defeat, despite his skill in the medical arts. In consequence, his disillusionment with samsara grew so great that even before his wife's passing he vowed to become a monk. In time, he was ordained at a Kadampa monastery where he absorbed all of Atisha's teachings. One day, while walking in the monastery grounds, he came across three beggars, one of whom mentioned the name of the great yogi, Milarepa. Merely upon hearing Mila's name, Gampopa felt such devotion that he fainted. In due course, he offered the oldest of the beggars gold in exchange for guidance in seeking Milarepa's whereabouts. Meanwhile, the clairvoyant Milarepa told the students and patrons surrounding him that a monk physician was on his way, and that whoever saw him and offered him lodging first would obtain liberation. When a lady named Tsese became the first to encounter Gampopa, she told him what Mila had said, at which point Gampopa felt a twinge of pride. “I must be important,” he thought, “if the Guru would say that the very sight of me would confer liberation.” Again, Mila's wisdom eye informed him of his destined disciple's state of mind, so to purify Gampopa's vanity he had him taken to a rock cave where he had to cool his heels for two weeks! When Gampopa finally reached the state of no hope-no fear, Milarepa sent for him, and gave him the teachings on tummo, the yoga of the psychic heat. As he practiced in retreat, Gampopa cycled through a series of supra-mundane experiences, each of which he reported to his guru. And every time Milarepa would stabilize him by advising him not to take these phenomena seriously as they were neither good nor bad. He would also give Gampopa further instruction and yogic exercises to perform until finally Gampopa could meditate on bare rock without discomfort. Though Gampopa would have liked to remain near Mila for the remainder of the latter's life, the guru commanded him to go to Gampo Dar in central Tibet and gather students there. Just as Gampopa was leaving, Milarepa gave him a final living instruction which he called his most precious teaching. With that he lifted his robe to reveal the callouses that had developed on his bottom as a result of meditating for so many years on bare rock. “There is no more profound teaching than this,” he said in parting. “This is the essence. Therefore, exert yourself unceasingly.” In the end, after reaching Gampo Dar, Gampopa attracted more disciples than had ever in Tibet's history been gathered in one place at one time -- over fifty thousand. Among these were disciples who would themselves become lineage heads, including Phagmodrupa, founder of the Phagdru Kagyu, and a prematurely gray-haired U Se, who would ultimately become the first Karmapa. To them Gampopa was able to offer his unique blend of the Lam Rim (stages of the path) and Lojong (mind training) teachings he had received from his early training with Atisha's Kadampas, and the Mahamudra (Great Seal) and Six Yogas of Naropa which he had later received from Milarepa. In addition, Gampopa broke with tradition by bestowing Mahamudra teachings on beings having no prior Tantric empowerments. In this way he compassionately brought many to realization who would otherwise have been deprived because they couldn't maintain the commitments involved in higher Tantra. Gampopa also demonstrated frequent siddhis (miracle powers). Once, he transformed himself into a huge Buddha as large as an entire mountain. Yet he still fit into his small room. When asked how he effected this, he explained: “This is the nature of phenomena. The small eyes of beings can see a whole mountain; a few inches of mirror can reflect an elephant; a bowl of water can reflect the full moon.” Gampopa was also known for his written works, most famous of which was The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, covering information on refuge, proper motivation, and the Six Paramitas (Perfections). “If you read this,” he said, “it is the same as encountering me personally.” But perhaps Gampopa's greatest achievement was that he became the father of the four elder (sometimes inaccurately called “greater”) lineages of the Dagpo Kagyu, each of which was headed by one of his major disciples. These were: the Barom Kagyu; the Phagdru Kagyu; the Karma Kagyu; and the Tsalpa Kagyu. Similarly, via his disciple lineage heads he became the grandfather of the eight younger (sometimes dubbed “lesser”) Kagyu orders. Gampopa passed away in 1153 to the pervasive smell of incense, the sound of celestial music, and the sight of overarching rainbows. After his cremation, his heart and tongue were recovered whole, thus leaving his disciples with visible symbols of his compassion and devotion to education in it's literal sense: the leading away from ignorance. Though it is tempting to examine the development of all the Kagyu schools, we will confine ourselves to the Karma Kagyu because it is this lineage whose tradition has culminated in the establishment by Lama Norlha Rinpoche of our Kagyu Drupgyu Chodzong.

Further information on Marpa, Milarepa and Gampopa may be found in the following texts: The Life of Marpa the Translator, by Tsang Nyon Heruka (Prajna Press) The Life of Milarepa, trans. by Lobsang Lhalungpa (Shambhala) The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, trans. by Garma C.C. Chang (Shambhala) The Life of Gampopa, by Jampa Mackenzie Stewart (Snow Lion) A Spiritual Biography of Gampopa, by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche (Namo Buddha Publications) |

|||||

© 2002 Junipur Press ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Please contact us for permission if your wish to reproduce any material found on this site, including text, pictures and code.

When we last looked in on our lineage forefather Naropa, he was residing at Pullahari monastery, awaiting the predicted arrival of his future student, the Tibetan Marpa

When we last looked in on our lineage forefather Naropa, he was residing at Pullahari monastery, awaiting the predicted arrival of his future student, the Tibetan Marpa  Marpa returned to India a second time to see his teachers again, review his understanding of their instructions, and gather a set of replacement texts to bring back to Tibet. Returning home he married, had a number of biological children, and attracted yet more Dharma “sons,” one of whom was Milarepa

Marpa returned to India a second time to see his teachers again, review his understanding of their instructions, and gather a set of replacement texts to bring back to Tibet. Returning home he married, had a number of biological children, and attracted yet more Dharma “sons,” one of whom was Milarepa  Gampopa

Gampopa